In this post Gary describes some quick ways to get students thinking about Question Three: “Why then and there?”

Question Three — why then and there? — is the hardest of the Four Questions. The Russians had a revolution in 1917. We can tell the story easily enough after consulting a decent textbook. We can say what Lenin, the leader of the revolution, was thinking by reading some widely available texts. To say with any degree of confidence and integrity why the Russian revolution happened when and where it did, on the other hand, we need to know an awful lot about Russia’s (and the world’s) economy and finances, its social institutions and political geography, and its culture. And we need to know how all these things were changing in the period leading up to the revolution. That inquiry project is not for the faint hearted.

The good news is that Jon and I nailed down the procedures for tackling Question Three in our book, From Story to Judgment. In the book, we share a rubric and a template that breaks down the steps for teachers and students, from finding correlations between contextual factors and the outcome we’re interested in to testing explanatory hypotheses on comparable cases. Follow the steps. It really works! The book lays out a case study you may already use in your modern world history classes: Japan’s modernization and China’s collapse in response to imperialism. Why then and there, indeed!

Still, gathering the materials necessary for students to formulate reasonable hypotheses about why events happen when and where they do, let alone to test them, is challenging and frequently laborious. Jon and I have started producing DBQs for 4QM teachers to use in the classroom to tackle Question Three in the classroom, like the one we designed for the book and others we have produced for clients. Once we’ve got a bunch ready, we’ll let you know when and where to find them.

Quick Question Three Activities

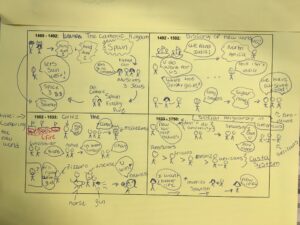

In the meantime, there are actually lots of quick and relatively simple ways to practice the logic of explanation — the Question Three thinking skill — without conducting a full-blown explanatory inquiry. Here are some fun classroom options.

- For a classic quick hit of Question Three, use your maps. Earlier this fall, I did two of these with my 9th graders. First, we looked at a map of river valley civilizations. I asked them to notice the pattern: early agrarian societies by living major rivers. Why there and not elsewhere? They supplied the plausible mechanisms: fresh water for farming and drinking, and water-control projects for ambitious leaders. Then, another Q3 puzzle: the ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Indus Valley civilizations were overrun by invaders. Their cultural and institutional traditions vanished. The Yellow River civilization became China. Why there and not in those other places? Again, our map tells a story (and our textbook tells it, too): China was relatively isolated by mountains, desert, and a vast ocean. Two chances to explain a difference with a difference in the same lesson!

- The key to the map activities is that they present lots of information in a condensed, visual form. Charts and graphs can do the same thing. Any time you have one, use it to identify correlations — patterned associations between events that may (or may not) reflect a causal relationship. For example, we reported here on a conference workshop we did in 2019 on political protests in Hong Kong, a topic that feels even more poignant now that the Chinese government has dissolved the remnants of independent politics there. The Financial Times made Question Three easy for us by gathering salient data in graphic form. Here’s one rich example:

That data is already old, but the trend still holds: Hong Kong used to be a major economic engine for China. Now, it plays a diminishing role in an increasingly industrialized country with many points of access to the global economy. Similar charts, widely available, show that China as a whole constitutes a much larger part of that global economy than it did back in 1997, when it was returned to China by Great Britain. Together, these charts help us to generate hypotheses about the timing of the central government’s abandonment of the “One Country, Two Systems” arrangement it promised to uphold in 1997. We can know how Chinese leadership justifies its crackdown on Hong Kong by reading its public statements. (That’s Question Two.) We can figure out the timing of its decisions by considering Question Three in light of these pithy charts.

- This one doesn’t even require charts or graphs: ask your students to identify the questions they’re asking and the claims they’re making. I recently did a judgment activity with my students. (That’s Question Four: What do we think about that?) As always, lots of what comes out in brainstorming in response to Question Four are claims about what will happen — great or terrible — if we choose a course of action. So, our deliberations about the virtues of political meritocracy as opposed to electoral democracy involved us in claims about how well each system deals with corruption and incompetence in leaders. Those are researchable Question Threes. We don’t actually need to know the answers in order to identify the core values and principles at stake in both systems. We do need to know what kinds of claims we’re making and questions we’re answering. Training students to get good at that makes them more faithful and effective discussion partners and much clearer thinkers.

- The same logic works for reading the typical tertiary sources we rely on for so much of learning in history classes. Our textbooks tell us what happened. They are also chock full of causal claims — answers to Question Threes — typically presented without evidence. Teach your students to identify those claims. Ask them what evidence would and should satisfy them that they’re true. That exercise alone will make them better, more astute readers.

There’s no substitute for practicing the full-blown inquiry we describe in the book. But excellent preparation for it is all around us. Enjoy!

G.S.