In January I posted about how I’m using The Writing Revolution by Judith Hochman and Natalie Wexler to help me teach writing. I often use 4-sentence stories as formative assessments to see if my students have understood the story that is at the heart of a unit, and this week I want to share another technique from The Writing Revolution that has helped me to do a better job of that: “Because,” “But,” and “So” sentences.

Common Conjunctions

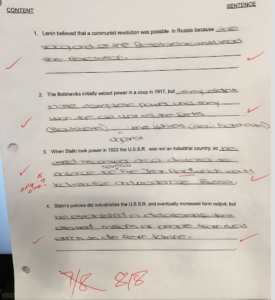

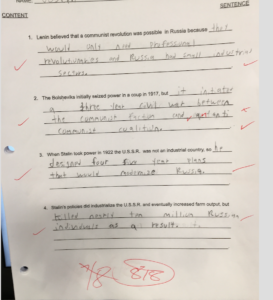

“Because, but, so” sentences are built around these three common conjunctions. The sentences start with a phrase before the conjunction, and students need to complete the sentence. As Hochman and Wexler explain, “because” sentences explain why something happened, “but” sentences have a contrast with the first phrase of the sentence, and “so” sentences describe a result of the first phrase of the sentence. The authors recommend having students use the same sentence stem for each type, but I modified the practice to fit the narrative four-sentence story form I use as a formative assessment. (See how “but” worked in that sentence just now?) I have been giving students four different sentence stems, using at least one of each sentence type, and they need to complete the sentence in a way that tells the story accurately and in correct academic English. Each sentence gets scored out of two points: one for accurate content, and one if the sentence is correct with no errors. You can see how I format that on the examples attached here: the content point goes in the left margin, and the sentence point goes in the right margin. So students know immediately what sort of error they need to be looking to fix if they’ve lost a point.

The sentence point has turned out to be a great teaching tool. It’s a binary score: if your sentence has no errors you get the point, and if it has even one you don’t get the point. I then allow revisions up to full credit, so students get practice noticing their common errors and correcting them. The most common errors are tense, subject-verb agreement, and missing small words. Focusing on single sentences has been tremendously powerful, because when students submit longer writing assignments their teachers (me included) don’t bother to correct most of these mistakes because there are so many of them. We tend to look past the writing errors and grade student thinking, which is often quite good. By contrast, the focus on four sentences allows students to get targeted feedback and repeated practice on important writing skills. It also turns out that students actually enjoy fixing their sentences. Once they know that they have to pay attention to the difference between “where” and “were” (a common confusion among my ELL students), for example, they start to do so and feel a real sense of pride when they catch and correct their own errors. I have one student from an immigrant family who was so thrilled the first time she completed a four-sentence story with no mistakes that she told me, “Mr. Bassett, this is going on the fridge!”

Another great teaching aspect of this exercise is that students cannot effectively complete the different sentence types unless they really know the story. It turns out that “but” sentences are especially challenging in this regard: students need to recognize that the first phrase of the sentence establishes something meaningful, and then they need to know something that qualifies or contradicts that something. In the examples posted here there are two “but” sentences: one requires students to know about the Russian civil war, and the other calls for knowledge of the cost of Stalin’s modernization program. Gary says that this activity should really be called “because, so, but” sentences, since “but” are the hardest ones — he’s right, of course, but it sounds better as “because, but, so.”

So once again, The Writing Revolution saves the day. Try it out, and let us know how it goes!