Question Three (“Why Then And There?”) is the most difficult of the Four Questions. It’s the most abstract, and the thinking it requires is generally unfamiliar to those of us not rigorously trained in one of the social sciences. (As a history major, I know this struggle personally.) It helps to remember that Question Three is inherently comparative. Answering it requires us to compare the story of a particular time and place with another story: either a story of the same place at a different time, or the story of a different place, or both. We’re looking for underlying factors that explains why the story changed, or why the stories of two places turned out differently. The formula we teach to students is, “explain a change with a change or a difference with a difference.”

This year I’m teaching modern world history, and the stories of China and Japan’s responses to Western imperialism offer a golden opportunity to practice Question Three thinking. These two stories create a kind of natural experiment. Consider: we have two Asian countries, both largely isolated from the outside world, and both initially contemptuous of Western culture and products. Both are forced open to international trade by Western military power, and leaders in both countries debate policy options: Should they resist Western domination by strengthening their traditional institutions and culture? Or should they try to strengthen themselves by dramatically changing their institutions and cultures to be more like the West? As most readers probably know, the traditionalists won the debate in China, and that country was largely dominated by the Western powers for approximately a century, from the mid-nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries. But the revolutionaries won the debate in Japan, which modernized and industrialized quickly after the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Japan was soon able to stand up to the West, ultimately establishing an Asian empire that lasted until Japan’s defeat in what the West calls “World War Two.”

This is a classic Question Three puzzle. We have two places that share many similarities, who encounter the same problem in the same era. Yet they react very differently, with starkly different results. Why did China stick with tradition, while Japan opted for revolution? On my unit sheet the Question Three is phrased like this: “What explains why Japan responded to contact with the West so differently from China?”

Working in their small groups, my students did a great job thinking through this puzzle this year. Here’s how they did it.

Step One: Define The Explicandum

We started out by reviewing our answers to Questions One (“What Happened?”) and Two (“What Were They Thinking?”) for China and Japan in the nineteenth century. Answering these questions had been the focus of our unit so far, so this quick review took only a few minutes. We then re-read the Question Three, and I reminded the students of the formula, “Explain a change with a change or a difference with a difference.” In this case, we were seeking to explain a difference between China and Japan’s responses to the West. So I had them turn to their groups and gave them ten minutes to see if they could identify any differences between China and Japan that might plausibly explain why the countries responded so differently to contact with the West.

In my first circuit around the room I heard several students making a very common error: they tried to answer Question Three by narrating the story, or stating what leaders in each country were thinking. These students said things like, “The Japanese responded differently because they were more open to Western ideas.” This is not an answer to Question Three, it is a re-statement of the explicandum — the thing we seek to explain. (Social scientists would call this the “dependent variable.”) We already know that the Japanese leaders were more open to Western ideas than the Chinese leaders. Question Three asks why that is. I was able to help these students see their mistake quickly; in every case there were other students in the group who had also seen the error for what it was and they chimed in to help. Good Question Three thinking starts with clearly defining your explicandum.

Step Two: Identify A Plausibly Relevant Change Or Difference

Once you’ve identified your explicandum, the next step is to identify a change or difference that could plausibly be related to it. In this case, my students quickly identifed two differences between China and Japan that they thought might be related to their different responses to the West. First, they suggested that while both countries were nominally isolated from the West, China had maintained and managed a subservient Western presence in their country for centuries. As Commissioner Lin’s 1839 letter to the English monarch notes, Western traders had always been “submissive” to Chinese demands for tribute and had acquiesced to Chinese regulations. My students had no evidence of a similar Western presence in Japan, and our sources had emphasized that the Japanese were astonished by the power of Commodore Perry’s warships when they arrived in the capital city in 1853. Their reaction suggests that the Japanese had not had significant contact with the West for a long time. And second, they noted that China is an enormous country, while Japan is a relatively small island nation.

Step Three: Describe A Mechanism That Shows How The Change Or Difference Works

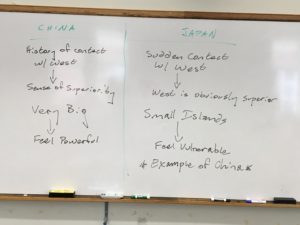

The next step in the Question Three thinking process is to explain how the change or difference you’ve identified actually works to produce the outcome you’re curious about. What’s the connection between the underlying factor(s) and the explicandum? The photo below shows my students’ answers to that question for size and contact with the West. They posited that China’s history of contact with the West might have bred a complacent sense of superiority that was difficult to overcome, even when Western powers demonstrated their military prowess. By contrast, a sudden introduction to Western gunboats might have impressed Japanese leaders with a sense of inferiority that made them more open to change. And they hypothesized that the size of China might have also contributed to an unwarranted feeling of power among the leadership: after all, the country would obviously be difficult to conquer. By contrast, Japan’s small size may have led its leadership to feel vulnerable.

In talking through these two differences my students noticed a third difference: Japan had the example of China to learn from. When Japanese leaders visited China in the late 1800s they were shocked to see the once-dominant regional power weakened and exploited by foreigners. Perhaps this example of what not to do helped to inspire support for the Japanese revolutionaries who urged their countrymen to embrace Westernization.

Process, Not Answers

I emphasized to my students, and I now emphasize to readers, that I don’t really know the answer to this Question Three. The answers provided by my students seem plausible to me (although a quick internet search while I was writing this post turned up at least one article that suggests the “more contact / less contact” difference is entirely incorrect, and the mechanism exactly backwards!). I especially like the “example of China” explanation, and I have some other ideas about contrasting social structures in China and Japan and the importance of the Samurai Class, but I don’t know enough about this history to have a settled opinion. I’m blogging about this lesson because it was a great example of tenth graders demonstrating Question Three thinking, not because I’m sure they’re right about their answers. (If readers have ideas on this, I’d love to hear them; email us at info@4qmteaching.net.)

Question Three is challenging. But with practice, and with clear coaching on the three steps in thinking described above, even high school students can think like social scientists!

J.B.