Last week, Jon wrote about Graham Delano, an awesome young teacher at Nashville Classical Charter School. Graham’s students had learned a story, but didn’t know how to begin retelling it. Graham called them back and identified the actors in their story — Native Americans, led by Chief Joseph, and the American military. That prompt allowed students to do what skillful narrative requires: say who did what, in an active voice.

Graham’s students aren’t the only ones who need help with that task. (In our book we have a whole chapter on historical narratives.) My own students are much older than Graham’s, and they too struggle to narrate historical events in a way that highlights the actors. Their default mode is to list events: this happened, then that happened. As if the people of the past were spectators watching events unfold before them!

Note Taking: One Source of Bad Narratives?

I’ve begun to wonder if the way we teach history, or at least the way I do, trains students the wrong way. I have a particular culprit in mind: note taking.

Notes on reading and lecture can end up looking a lot like lists. And if you don’t know better, you can think that getting down the names and dates of events is the main purpose of notes. In fact, as Dan Willingham has clarified, the goal of notes is to remind us of stuff we’ve thought about, so that we can think about it again.

For historical narratives, we do want to think about and remember events, but not independent of the people who did those things we now designate “events.” Our narrative memory is most meaningful and stickiest if we make it a package deal: who-did-what.

But that’s not my students’ default. I’ve tried a variety of ways of addressing this problem in my own classroom. One of them is substituting more engaging narratives than the textbook when I can find them. For my origins of Islam unit, for example, I use two chapters from Tamim Ansary’s Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (Public Affairs, 2010). Ansary has written for textbook companies, so he knows our audience. His book is different, though: it foregrounds the actors in the narrative.

I’ve found that even that isn’t enough to keep students from taking reading notes as bulleted lists of events. So I came up with a hack that worked reasonably well. It’s simple, and can work even with relatively dry textbook readings.

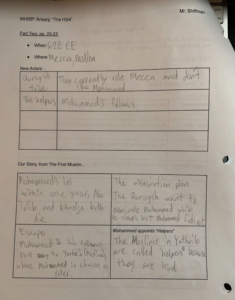

I made students a printed, four-page notes template. I designed each page to capture notes on a segment of the story, from Muhammad’s birth in 570 CE to his death in 632 CE. Each page had three sections for students to complete.

- Part One: When and Where?

This one’s simple: when is the action taking place, and where? The whole story takes place in Mecca and Medina, between the years I listed above. Students just need to lock in the context for the chunk of the story they’ve read.

- Part Two: Main Actors

This section has two columns, one for the names of actors who do things in this chunk of the story, and one for a brief description of each of these actors. The first chunk includes Muhammad, Abu Talib, the uncle of Muhammad who adopted him after his parents died, and so on.

- Part Three: Our Story So Far

For this template, I framed the narrative notes section as a storyboard. So, below “When and Where” and “Main Actors” sits a little four-box storyboard. I filled in the title of the last box for each of the four mini-storyboards so that students would know where to end up. They had to make titles for the other boxes and then write a brief sentence describing who did what below it.

Here’s an example from Max, from page two:

How’d It Go?

When we debriefed the reading, which we began in class and students completed for homework, I asked about the notes template. We’d done traditional outline notes on similar readings, and have storyboarded plenty. I asked if this worked for them.

Hallie volunteered immediately that the “main actors” section helped a lot. I checked during the class, and she in fact knew the story well. (She tracked Omar, who is a bit player in this chapter but ends up becoming the second Caliph and a crucial figure in the development of Islamic doctrine and the Islamic empire.)

One of the comments I ended up making on lots of the templates was about the overuse of pronouns. The storyboards were full of sentences that said “He” did this or “they” did that. Still, the list of main actors gave me more confidence that students had a particular “he” or “they” in mind when they took their notes. (As I pointed out, whether they’d remember who “they” were when they studied from these notes is a separate question.)

Ideally, I’ll wean my students off my templates and have them create their own in their notebooks from here on out. They can make a section for “where and when” and a section on who’s making history before they record events. The fact is, a storyboard is just an outline laid out on a page for visual effect. They can make their “storyboard” vertical and proceed chunk by chunk. On the other hand, I do like forcing them to read and learn the section before writing their notes. That requires more thinking about the action before writing stuff down.

G.S.