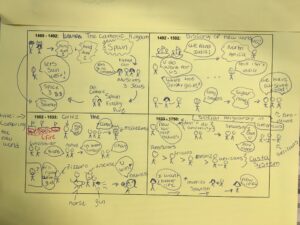

In this post Jon describes how a storyboarding activity helped his students to make sense of lecture notes they’d taken on the Spanish Empire.

This week in my tenth grade AP World History class we were learning about the Portuguese and Spanish Empires of the 15th – 18th centuries. I gave the same lecture on the Spanish Empire to my two sections, first period and third period. I’m a big proponent of lecture as a teaching technique, especially for Question One, “What Happened?” A successful lecture is just a good story well told, and I was pleased with how well mine went. Most of my students were attentive, and most took pretty good notes, writing more than I had on the board, and some asked good questions.

But critics of lecture as a teaching technique are correct that unless we ask students to do something with the information they’ve noted, we can’t be sure of how much they’ve actually learned. So I followed my Spanish Empire lecture with a classic 4QM classroom activity: I had my students retell the story by illustrating a four-box storyboard.

Storyboards As A Classroom Learning Activity

At 4QM Teaching we train teachers to use storyboards in unit planning, but we also use them a lot as a classroom teaching technique. They are a brilliant tool for forcing students to use information they’ve learned (whether from a lecture, reading, or some other source) to create a coherent and accurate historical narrative. Storyboarding is a powerful learning technique because it requires students to make decisions. They need to decide what information is relevant and important enough to include on their storyboards, they need to create illustrations that reflect a clear and accurate understanding of the story, and they need to decide how to divide the story into four sequential chapters that cover the whole assigned time frame. Making all of those decisions, especially if students are working with a partner or small group, requires a lot of interacting with and thinking about historical content.

From the teacher’s perspective, storyboards also function as an excellent check for understanding. Listening in on student conversations and asking questions about illustrations quickly reveals what students understand and don’t about the historical narrative you think you taught.

Storyboarding can be scaffolded up or down, depending on what your students need. Many of my tenth graders don’t yet read or write on grade level, and it’s still early in an unusual post-pandemic school year. (If you’re a teacher, you know what I’m talking about — it’s been a rather bouncy fall, right?) So I made this storyboarding task a bit easier by giving students the date range for each box, keyed to turning points in the story I had articulated in my lecture. You can make the task harder by just giving a start and end date, and having students decide how to break the story into four chapters, or by giving no dates at all and having them make all the decisions.

Students were assigned to create a title for each box that reflected the events of that box’s date range, and to illustrate the box with appropriate pictures. I emphasized that art is not being graded (my “people” are usually just lollipops), but comprehension is. I scored the storyboards out of eight points: one each for the title and illustration in the four boxes.

How’d It Go?

The results were interesting, and humbling. Here’s some of what I noticed.

First off, nearly everybody enjoys storyboarding. It’s fun to talk with your classmates, and it’s fun to draw. Second, the conversations about what to put in each box are great. Students pore over their notes, trying to figure out why I chose the dates for each box, arguing over what goes where, and debating appropriate titles. I had a lot of students waving and beckoning, asking me to “Check mine! Check mine!”

Second, a significant percentage of my students had taken what looked like good notes, but they didn’t fully understand them until they had to use them to retell the story. Students were confused about who was a Spaniard (Hernan Cortes) and who was an indigenous American (Moctezuma). They were confused about the sequence of events (the “Columbian Exchange” happened over many years, and after 1492). Storyboarding was an excellent way to surface and correct those misunderstandings.

Third, because of scheduling, my third period class did the storyboard on the same day we finished the lecture, while my first period class did it the following day. The students who did it the same day had a much easier time of it. If there’s a cognitive scientist reading this, I’d love to know which you think is more effective for learning — I suspect waiting a day actually produces more retention, but I don’t actually know that. Comments welcome!

Fourth, drawing is a great way to have students whose written English is not strong express their understanding of historical narrative. As I mentioned before, many of my students are not yet strong writers.This activity put a premium on thinking about the history, not on thinking about spelling, sentence structure, word choice, or all the other things that go into writing.

I’m posting a picture of a sample storyboard from a strong student below. The box titles are:

1469 – 1492: The Catholic Kingdom

1492 – 1502: Discovery of New World

1502 – 1533: Conquering the New World

1533 – 1750: Social Hierarchy in Americas

If you’ve never tried storyboarding with your own students, I highly recommend it. We talk about it extensively and include an example from American history in our book, From Story To Judgment, and you can always reach out to us through the comments or by emailing us at info@4qmteaching.net if you’d like to talk more about it.

J.B.