About a month ago I wrote a post about China and Japan’s different responses to Western imperialism, and how that made a perfect Question Three puzzle. (You can read that post here.) Today I’m circling back to that topic because I recently had a conference about it with student, and I think the conference was helpful in illustrating a fun and interesting phenomenon about Question Three.

Explanatory Turtles

Francis Fukuyama is one of my favorite authors (I know, I know, you think he’s wrong about The End of History, but we can talk about that later), in part because he has a wry sense of humor. In his book The Origins of Political Order he attempts to explain why human societies have developed as they have, and at one point he recounts the apocryphal story of a cosmologist who is giving a lecture on the structure of the universe. As she is describing the orbits of the planets around the sun she is interrupted by a man in the audience who tells her that she is wrong, and that the earth is in fact balanced on the back of a giant turtle. Without missing a beat, the cosmologist replies, “Ah yes, sir. But what is that turtle standing on?” The man replies, “It’s no use, professor! It’s turtles, all the way down!”

Fukuyama recounts this tale to illustrate the problem of social scientists trying to explain things. I asked my students to explain why China and Japan reacted differently to Western imperialism, for example, and got some plausible explanations. But as Fukuyama notes, “the turtle one chooses as an explanatory factor is always resting on another turtle farther down.” How do we know when to stop explaining? Fukuyama goes all the way back to human biology in his search for “a Grund-Schildkröte (base turtle) on which subsequent turtles can be placed” (438). We don’t usually have to go that far in our high school history classes, but we do need to go far enough in our search for base turtles to get past Questions One and Two.

Question Two Is Not Your Base Turtle

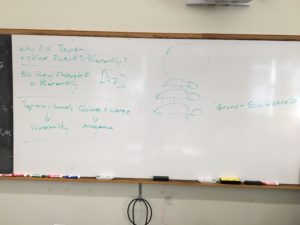

A common error in answering Question Three is to actually answer Question Two, which was what my student had done on his summative assessment. Answering Question Two is never a good base turtle – it’s simply restating the explicandum, or the outcome we seek to explain when we ask Question Three. This photo of the board after my student conference shows the levels of thinking involved in a good Question Three puzzle, and the common mistake of stopping at Question Two.

On the top left is the Question Three: Why did Japan and China react differently [to Western imperialism?]. That’s the equivalent of the earth I drew on the top right: the circle on top of the turtles. This is the explicandum, the outcome we seek to explain.

Then below that is my student’s first answer to the question: “Japan and China reacted differently because they thought differently.” I put a Q2 in brackets next to that answer, because it’s not an answer to Question Three, but rather to Question Two, “What were they thinking?” This is the equivalent of the first turtle that I drew underneath the earth on the right. It seems like an explanation, but if you think about it for a moment you’ll see that it’s just a restatement of the explicandum. Obviously the Japanese and Chinese leaders thought differently — if they thought the same way, they would have acted the same way. Question Three asks us, “Why did the leaders think differently? What difference(s) between Japan and China made it more likely that their leaders would think differently in the ways that they did?” Question Three is the cosmologist saying, “Ah yes, sir. But what is that turtle standing on?”

On the bottom left is my student’s “base turtle:” a geographic explanation for why the leaders of Japan and China responded as they did. The student has identified a plausibly relevant difference between Japan and China, and has described a mechanism that links that difference to different ways of leadership thinking. Japan is small, and perhaps that led its leaders to feel vulnerable when confronted by the West, thus more willing to make significant changes in order to avoid being dominated and exploited. China is big, and perhaps that led its leaders to feel arrogance towards the West, and thus less willing to make significant changes in response to Western aggression. I’ve got an extra turtle in the diagram on the right, but the point is clear: when you’re dealing with Question Three, you’ve got to get down to a base turtle, or you don’t really have an explanation. The Question Two turtle needs to be standing on something else.

See You This Fall!

This will be our last blog post of this school year. We’re thinking of trying a podcast this summer, but in any case we’ll be back in this space in August. Fee free to email us with ideas for posts, suggestions for guest bloggers, or questions about anything you read. Thanks for reading!

J.B.