People who study memory know that drawing a picture is one of the best ways to remember something. But how often do history teachers use this powerful memory tool with their students? Most of us don’t do it often enough. An intentional use of student-generated images can help students to remember important historical events much more effectively than more common techniques, such as study guides, review sheets, or organizers that list “key terms” or “identifications.” Drawing pictures can also be a lot of fun for teachers and students.

A recent New York Times article about memory explained that “the three-act technique of picturing something in your mind, putting pen to paper to draw it, then looking at your drawing is a powerful memory trick that outperforms other ‘strong’ mnemonic strategies.” In an earlier blog post I wrote about the website “Sketchy Medical,” which uses funny cartoon mnemonics to help medical students learn and remember the information they’ll need to pass their licensing exams. Clearly, a lot of smart people have discovered that drawing pictures helps us to remember important things.

History teachers and students can make use of this insight by combining pictures with another ancient and effective memory technique: story-telling. If you’ve ever attended one of our 4QM workshops, or if you’re a regular reader of this blog, you know that we believe that good history teaching and learning starts with a story. We lay out our unit-level stories on a six-box storyboard when we’re planning, and we often use four-box storyboards for formative assessments with students. Here’s how it works. After the kids have learned what happened in an important event, you ask them to make an illustrated storyboard of it. You can give them the start and end dates or make them pick their own, and tell students that each box of their storyboard has to have a title, a date range, and a picture that effectively symbolizes that portion of the story. (Reassure your students that the artistic merit of their illustration is irrelevant to its power as a learning tool and memory aide.) I typically have students work in small groups on this; the group talks together about the titles and date ranges, striving for consensus. Then everyone makes their own storyboard and draws their own pictures. You can take it one step further and have a few students use their storyboards to tell the story of the event to the class in brief oral presentations.

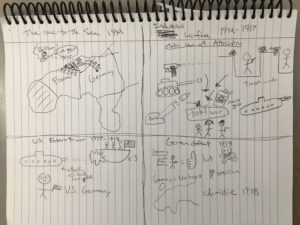

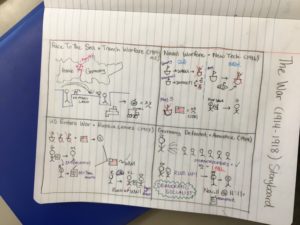

Here are a couple of recent storyboards of World War One from my tenth grade modern world history class. (You may have to increase the size of your browser window to see them well – I apologize for not knowing how to make them the right size, or how to crop the blue seat out of the picture on the right. Sigh.)

Notice how these students made different choices about how to chapterize the story, and included different specific facts in each box. In addition to assessing student understanding of the narrative, storyboards can also be springboards into discussion of these kind of historian’s decisions. Why did the second student decide to include trench warfare in the box number one, while the first student included it as one example of “industrial warfare” in box number two? Why did the second student include Russia’s collapse, but the first student omitted it? Storyboards enable conversation about what how and why different narrators choose to tell the story differently.

We live in the twenty-first century, so of course there’s an online storyboarding tool that allows you to make digital storyboards; here’s a link to their homepage: StoryboardThat. I doubt that making a digital storyboard is as good an aide to learning and memory as drawing your own pictures, but some students might find the online version more engaging than working with a pencil.

Drawing pictures is a powerful memory tool that’s fun and easy to use. History teachers and students should use it regularly to leverage the power of pictures.

J.B.